Slider

Pravda statunitense: JFK, Richard Nixon, la CIA e il Watergate

Le Schede di Ossin

Tagline

Le Schede di ossin, 10 agosto 2024 - Cinquantadue anni fa lo scandalo del Watergate, spacciato come un'alta dimostrazione…

More...

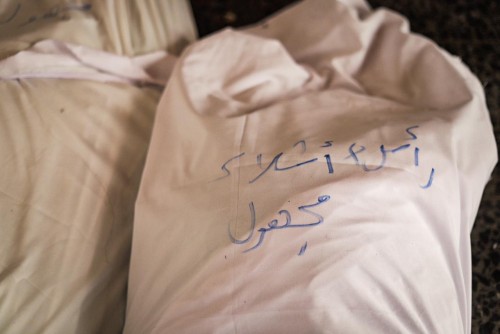

Massacro israeliano di Fajr: ogni sacco da 70 kg di resti umani è un martire

Storie di genocidio

Tagline

Storie di genocidio, 12 agosto 2024 - I corpi dei Palestinesi uccisi nell'ultimo massacro israeliano a Gaza sono stati fatti…

More...

"Ho paura di morire": i tanti modi in cui gli uomini ucraini cercano di sfuggire al servizio militare

Le guerre dell'Impero in declino

Tagline

Le guerre dell'Impero in declino, 12 agosto 2024 - Aggirando (col VPN) la censura dell'Unione Europea, vi presentiamo questo…

More...

Tommy Robinson e altri agenti sionisti dietro le rivolte razziali in Gran Bretagna

Gran Bretagna

Tagline

Gran Bretagna, 15 agosto 2024 - Ci sono indicazioni inequivocabili che il fervore anti-musulmano che ha devastato la Gran…

More...

Aime VI, Giove e il Biondastro con un buco nell'orecchio

Marocco

Tagline

Marocco, 20 agosto 2024 - Una storiella divertente, ma non fatua, di Ahmed Bensaada, che vede Aime VI (il…

More...

L’ultimo spettacolo: l’operazione ucraina in territorio russo

Le guerre dell'Impero in declino

Tagline

Le guerre dell'impero in declino, 23 agosto 2024 - L'operazione ucraina in territorio russo arrecherà solo danni a chi…

More...

Dall'11 settembre al 7 ottobre: si spegne la finta "guerra al terrorismo"

La guerra in Medio Oriente

Tagline

La Guerra in Medio Oriente, 15 settembre 2024 - Per anni, gli Stati Uniti hanno portato avanti il programma di…

More...

Come la scusa della "diffamazione del sangue" tappa la bocca all'Occidente sul genocidio di Gaza

Le Schede di Ossin

Tagline

Le schede di ossin, 12 agosto 2025 - Quanto più depravate sono le azioni di Israele, tanto più denunciarle viene…

More...

.png)